What Is The Heroine’s Journey And Why Does It Matter?

The “Hero’s Journey” has long served as the archetypal template for man’s development in myths- but what happens if the hero is a woman?

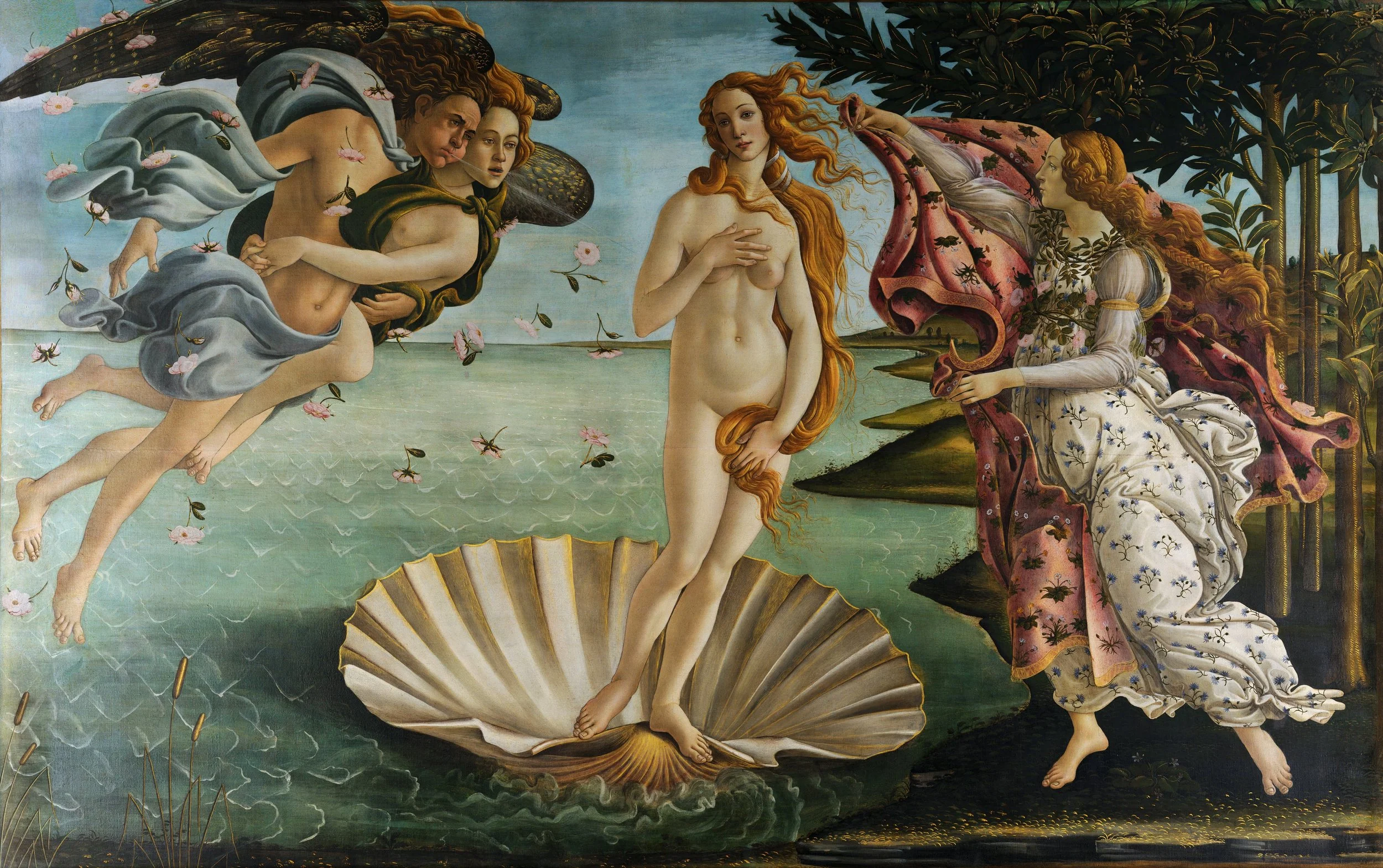

Photo from Wikipedia Commons

The Myth of The Strong Female Lead

Recently, a friend sent me a fantastic article by writer and actress Brit Marling, entitled, “I don’t want to be the strong female lead.” Marling, who moved to Hollywood at 24 to become an actress, shares her experiences auditioning for roles like “Dave’s wife” or “Robot girl: a remarkable feat of engineering; her breasts are large and she’s wearing a red sweater.” Though she works hard to attain lead parts, upon getting them she is disappointed: “The more I acted the Strong Female Lead, the more I became aware of the narrow specificity of the characters’ strengths — physical prowess, linear ambition, focused rationality. Masculine modalities of power.”Marling’s article does a great jobhighlighting the dysfunction of how women are currently portrayed in Hollywood, but when posed the question of what the replacement should be, she only says,“these are not yet solutions. But they are places to dig.”

The question of what a distinctly female hero would look like and do is not new; ever since the Hero’s Journey was described by Joseph Campbell, women have wanted to know its female counterpart. Campbell was asked this exact question many times during his lifetime, and he cryptically responded:

“Women don’t need to make the journey. In the whole mythological tradition, the woman is [already] there. All she has to do is to realize that she’s the place that people are trying to get to.”

Though this answer angered many of Campbell’s female colleagues, who considered it a dismissal of the feminine experience, the more I investigated it, the more true it seemed.

The key part of Campbell’s answer is his emphasis on the power of the feminine realization. In his book “Goddesses,” Campbell elaborates on this idea by describing the feminine as a transformational principle: “Her main themes are initiation into the mysteries of immanence experienced through time and space and the eternal; transformation of life and death; and the energy consciousness that informs and enlivens all life.” Poet David Whyte illustrates the feminine approach when he tells the story of the Tuatha dé Danann, a mythical Celtic race of Goddess worshippers. When a more brutal race invaded Ireland, the Tuatha dé Danann fought them off against overwhelming odds. Facing a final battle, they came out in their most beautiful clothes, lined up in battle formation, and “turned sideways into the light and disappeared.” As Whyte and many listeners interpret it, turning sideways into the light is:

“…the realisation that there are some encounters that are damaging to all involved in them: no one wins a war. Faced with such an exchange, to turn sideways into the light is to seek another, more whole form of relationship. It is to reject the ground rules of the conversation as they have been laid out by your antagonist and choose another path which will extend, not diminish your integrity.”

The Heroine’s Journey, I’ve come to believe, is a shift in perspective and awareness that changes the meaning of an entire situation. It doesn’t necessarily involve any external force or action but- like the difference between information and energy- it rearranges the pattern entirely.

The Hero And Heroine Together

The Heroine’s Journey doesn’t often operate in isolation. The best framework I’ve found that demonstrates this is laid out by Carole Pearson in her book, “Awakening the Heroes Within.” In her book, Pearson lays out the twelve archetypes of the traditional Hero’s journey- the Innocent, the Orphan, the Warrior, and so on- but arranges them in an ascending spiral progression. As she describes it, “the pattern is more like a spiral: the final stage of the journey, epitomized by the archetype of the Fool, folds back into the first archetype, the Innocent, but at a higher level than before.” As an example of this progression, Pearson describes how the Warrior archetype manifests differently at various levels. While initially, the Warrior may simply fight others or fight to preserve an ideal- such as a soldier defending liberty- the highest level of Warrior has “little or no need for violence and a preference for win/win solutions.”

In Pearson’s framework, the Heroine’s Journey is the shift from one level of archetypes to the next. It is the moment the individual puts down his sword and realizes that there is no need to fight in the first place to achieve his goal.

But even if we can theoretically understand the Heroine’s Journey and how it fits together with the Hero’s, the question remains: What does this look like in real life?

Modern Heroines

Most historical heroines- such as Cleopatra or Josephine- used their sexuality to control the men and action around them. Nowadays, the idea of feminine power is making a resurgence in ways that have expanded far beyond pure sexuality. As I’ve described before, former dominatrix Kasia Urbaniak has dedicated her career to teaching women the rules of power dynamics. The crux of her technique is that when women are conscious of the movement of attention and their ability to shape it, they gain a psychological power at least as influential as physical power. In the field of art, Marina Abramovic has carried this idea to the extreme: Her art pieces, such as “The Artist is Present,” are based on shaping the atmosphere and audience-artist relationship to evoke a strong emotional response. What both Urbaniak and Abramovic teach is that women can exert powerful influence by consciously shifting intention and relationship dynamics, as opposed to using brute force to achieve a goal.

To see the value of this approach, consider the real-life example of the Red Hook Community Justice Center in Brooklyn, NY from the book “The Art of Gathering” by Priya Parker. The founders of the center decided that they wanted topursue the goal of improving behavior rather than merely punishing it.To that end, they made changes such aslowering the judge’s bench to eye level so he can interact personally with litigants, choosing large windows and light wood to create a light atmosphere, and assigning a social worker to perform a full assessment of the accused prior to the trial. Already, the Justice Center has seen improved results in the neighborhood where it is located:

“ It reduced the recidivism rate of adult defendants by 10 percent and of juvenile defendants by 20 percent. Only 1 percent of the cases processed by the Justice Center result in jail at arraignment.”

Whether the field is art, sex work, or even criminal justice, I believe these are all real life examples and manifestations of the Heroine’s Journey at work. They are conscious shifts of perspective, allowing goals to be achieved with outcomes that are best for all involved.

Our World Reflects Our Stories

Marling’s article reminded me that the world we get is often a direct reflection of the stories we tell ourselves, personally and collectively. And often when societies are most in need of change, the old stories stop working and become stale. As Pearson wrote of her archetype framework:

“ Today… many people have negative feelings about the Warrior archetype. Yet it is not the Warrior archetype that is the problem; it is that we need to move to a higher level of the archetype…It takes high-level Warriors — whose weapons include skill, wit, and the ability to defend themselves legally and verbally or to organize support for their cause — to keep predatory, primitive Warriors in place.”

I believe that once we understand the role of the feminine archetype and the Heroine’s Journey, we can share stories and films that honor them. When we create characters that are capable of perspective shifts and reframing the trajectories of their own development, we’ll be educating ourselves on how to do the same in our own lives.